| The history of Duchamp's Bicycle Wheel has been frequently recounted and is sufficiently known. One aspect, however, has often been considered too little: the usability of this peculiar apparatus. | Click to enlarge |  | Marcel Duchamp, Bicycle Wheel, 1913

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris | Rhonda Roland Shearer has recently pointed out that at least the second version of the Roue de Bicyclette, created in 1916 in New York, is statically an extremely fragile object. Could, Roland Shearer ponders, the combination of front-wheel fork, rim and a stool be "an experiment and schematic diagram of chance". Duchamp himself, during his lifetime, never ceased to stress, with ostentatious calm and persistence, the incidentalness and the insignificance of his invention trouvé. Even though today the Bicycle Wheel is regarded as one of the central incunabula of the ready-made-idea, we now know that originally it had little in common with the future ready-made . According to Duchamp, the 1913 original as well as the 1916 version of it were rather intended to please him personally, to be "the 'gadget' for an artist in his studio." One of the statements used by Duchamp in several interviews is to be remembered in this connection - in the version that was handed down to us by Arturo Schwarz: "To set the wheel turning was very soothing, very comforting, a sort of opening of avenues on other things than material life of every day. I liked the idea of having a bicycle wheel in my studio. I enjoyed looking at it, just as I enjoyed looking at the flames dancing in a fireplace. It was like having a fireplace in my studio, the movement of the wheel reminded me of the movement of the flames ." Clearly, the analogy to an open fire was not chosen arbitrarily. Duchamp, with the flames dancing in the fireplace, found an easily intelligible analogon for the 'contemplative' effect that the spinning spoke wheel was supposed to have on him, at the time the first and only beholder and user - regardless of whether he had taken delight in the spokes' 'optical flicker' or in the object's supposed instability, provoked by the centrifugal forces acting upon it. Whether the spinning of the rim was "very soothing, very comforting" or rather, as Roland Shearer assumes, "hardly relaxing" it was originally part of the idea of the Bicycle Wheel. | Click to enlarge |  | Marcel Duchamp, Bicycle Wheel, 1913/64

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris | | | Should it not then be allowed, one may well ask now, to set the wheel turning even today, following Duchamp's instruction and thus to a large extent keeping the original idea alive? This, of course, strikes one as being quite a theoretical question, given the museum reality. Whoever encounters one of the Bicycle Wheel's replicas in a public collection today, be it in Cologne, Paris, Philadelphia, New York, Stockholm or elsewhere, is confronted with tabooing prohibition signs, exposing plinths and reprimanding museum attendants. This confirms not only the museum's inherent paradoxical logic of making history an actual experience by means of preserving it, but also the shift of meaning the idea of the Bicycle Wheel has been through in the course of the decades. Sidney Janis has the dubious honour of having introduced a first replica, namely the third version of the Roue de Bicyclette, into the context of an exhibition for the first time. He did so on the occasion of the "Climax in XXth Century Art"-exhibition early in 1951, thereby changing the object's intellectual status as well as the meaning and the function ascribed to it. The former "gadget" was de facto declared a designated ready-made within the canon of Duchamp's works. The artist himself had carried out the arrangement of the exhibits and had dated as well as signed and thus authenticated and authorized the replica of the Bicycle Wheel in the beginning of 1951. | | | Click to enlarge |  | | View of the Duchamp gallery,

"The Art of Assemblage" (October 2 - November 12, 1961), The Museum of Modern Art, New York

| Some years later, in the autumn of 1961, the same Janis-replica was displayed in the legendary exhibition "The Art of Assemblage" in the Museum of Modern Art, once more and unquestionably so within the context of the ready-made. The Bicycle Wheel, having been given the status of a museum piece, was transformed into a state of visually documenting the concept of the ready-made, which was regarded as being historical It was no longer necessary to set the wheel turning in order to be delighted by it; on the contrary, this was prohibited, as the American photographer Marvin Lazarus reported on the occasion of a photo shooting with Duchamp in the exhibition on 10 November 1961: "I wanted to move the Roue de Bicyclette so that I could shoot through it. Duchamp moved it. [...] the guard [...] ran over to me and asked if I had moved the object. Before I could answer, with a little smile, Duchamp said quietly, 'No, I did it.' The guard then turned on him and said, 'Don't you know you're not supposed to move things in a museum?' Duchamp smiled again and speaking very softly said 'Well, I made the object - don't you think it's all right for me to move it a little?'"" An interesting question, now, that the artist addressed to a presumably puzzled museum attendant. Had Duchamp been allowed to refer to his nominal and intellectual authorship in order to obtain the privilege of usage? This question seems too good to spoil with an answer. It raises, however, another, more general question that shall not remain unanswered. What would be gained by the average visitor to an exhibition and his aesthetic experience, if he too was allowed to set the wheel turning in an exhibition? As far as I know, this was the case only once in the history of exhibiting the various replicas. The touring exhibition "Art in Motion" (Dutch: "Bewogen Beweging", Danish and Swedish: "Rörlse i konsten"), stopping over in the Stedlijk Museum, Amsterdam, the Moderna Museet, Stockholm, and the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humblebaek, from the spring of 1961 onwards, among other optical and kinetical works of art put on display a replica of the Roue de Bicyclette, which, based on the 1916 version, had been built by Ulf Linde and Per Olof Ultvedt in May 1960. Pontus Hulten, at the time the Moderna's director, assured me that the visitors to the exhibition had been allowed to turn the wheel . The spirit in those days, Hulten said, had simply been a different one . A different spirit? Surely, rather, it was due to the fact that the replica, which had been built despite the lack of initial authorization, was of a low financial value. In consequence the curators Hulten and Sandberg could risk public use without having to fear too much damage . In order to return to the question I raised earlier: little would be achieved if the visitor was allowed to set the wheel turning. I will confine myself to giving two reasons, one of them concerning the curational problem: the history of the 20th century's participatory art shows that tactily involved viewers were always either overstrained with the offer of participation or unable to utilize the potential of the experience proposed to them. Allan Kaprow reported, for instance, that the visitors to his situational environment Push and Pull - A Furniture Commedy for Hans Hofmann from 1963 did not react the way he had hoped they would to his proposal to alter the furnishing. Robert Rauschenberg's Black Market, in which the visitors were supposed to exchange objects and document this exchange with a drawing, was ransacked in 1961 while on display in the exhibition "Art in Motion" . George Brecht had a similar experience when presenting his Cabinet made in 1959 - a cabinet containing several everyday objects. The intended epistemological experience, linked to the viewers' tactile participation, was thwarted by overzealous customers looting the Cabinet.

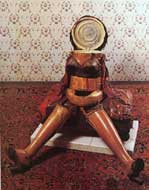

| | Click to enlarge |  | | Edward Kienholz, Cockeyed Jenny, 1961/62 |

|  | | Benvenuto Cellini, Saliera, 1540-43, Collection Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien | At the opening of Roxys, Edward Kienholz' legendary brothel environment, in the Alexander Iolas Gallery in 1963, one of the visitors of the vernissage urinated into the ash can of Cockeyed Jenny, one of the whore figure . The second reason concerns the origin of the Bicycle Wheel itself: it would be practically impossible for visitors to a spacious exhibition to recreate the intimate atmosphere of the studio where Duchamp had once been able to contemplate the movement of the wheel. It would be as if one allowed the visitors of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna to use, in an allegedly authentic manner, Benvenuto Cellini's Saliera in order to emulate François Primeur, long since covered with dust, at his sumptuous dining table. Historical events and situations may be portrayed vividly in a museum, but it is impossible to recreate them. Duchamp himself, however, was once more given the opportunity to set the wheel turning, for in 1964 the Roue de Bicyclette's shift or rather the establishment of its meaning entered its - for the time being - last stage. Duchamp had authorized Arturo Schwarz to produce, amongst accurate replicas of thirteen other works of art, an edition of the Bicycle Wheel, the number of copies being eight plus two. The production of replicas of the Roue which, in the fifties, amounted to only a few copies, thereby gained a new quality and quantity. The strategy of creating almost identical remades for the sake of representing the idea of the ready-made inevitably had to result in authenticity, originality, in the establishment of an aura and, finally, in artificiality. Every single piece of the Schwarz-edition, just as before with the replicas produced by Janis and Linde, had been affixed by Duchamp with the admonition of metaphysics, the personal signature. Signatures commonly authenticate the will of their absent author - unless they are forced from him, which is hardly to be assumed in the case of Duchamp/Schwarz. Duchamp had readily given his nominal placet to a definite authorization by signing the 'documents' presented by Schwarz. And soon the Bicycle Wheels, representing Duchamp's imagination, advanced triumphantly through the international museums, thereby strengthening their museumesque status as well. | Click to enlarge |  | | Photograph of Duchamp wearing a lampshade with Bicycle Wheel, 1951 © 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris | Duchamp, in the sixties, may have sat in New York and Neuilly, puffing away at his cigar and turning the wheel that had been given to him as an artist's copy from the Schwarz-edition. If so, then probably not without being amused by the course of things. The way the multiple Bicycle Wheels are displayed in the museums, however, was and still is traced out differently. The visitor of a museum or a gallery is no longer confronted with a "gadget" but with a remade representing the idea of the ready-made. The ease with which it had once been possible for Duchamp to set the wheel turning has been superseded by the complexity, the import, and the historicization of the ready-made-concept. Had Marcel Duchamp originally intended to create works that were not art, as he wrote in 1913 then the remades, on the other hand, bear witness to the affirmative force of an institutionalized operating system of art. The turning wheel of history has made the Bicycle Wheel an artefact. Reciprocally, the latter has lost its drive.

notes 1. Roland Shearer, Rhonda: Why is Marcel Duchamp's Bicycle Wheel Shaking on Its Stool?, in: www.artscienceresearchlab.org, December 1999; see also her reply to What makes the Bicycle Wheel a Readymade by Yassine Ghalem, in: www.toutfait.com, vol. 1, no. 2, May 2000; and "Marcel Duchamp's Impossible Bed and other 'Not' Readymade Objects: A Possible Route of Influence from Art to Science, Part I," in: Art & Academe 10, no. 1 (Fall 1997), pp. 26-62; Part II in: Art & Academe 10, no. 2 (Fall 1998), pp.76-95 2. See Duchamp in Cabanne, Pierre: Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp. New York: Wiking, 1971, p. 74 and Schwarz, Arturo: The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp. 3., revised and expanded ed. New York: Delano Greenidge Editions, 1997, p. 588. 3. Marcel Duchamp, quoted from Siegel, Jeanne: Some late Thoughts of Marcel Duchamp. In: Arts Magazine, Vol. 43, New York, December 1968/ January 1969, p. 21, here quoted from Daniels, Dieter: Duchamp und die anderen: Der Modellfall einer künstlerischen Wirkungsgeschichte der Moderne. Cologne: DuMont, 1992, p. 208. 4. Duchamp, quoted from Schwarz [1997], ibid., p. 588. 5. Duchamp, quoted from Schwarz [1997], ibid, p. 588. 6. Roland Shearer, Rhonda: Why is Marcel Duchamp's Bicycle Wheel Shaking on Its Stool? In: tout-fait, Vol. 1, Nr. 1, December 1999. 7. Following Buettner, Stewart: American Art Theory 1945-1970. Michigan Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1981, p. 109. 8. This is not only confirmed by the photographs documenting the mode of presentation but also by an entry in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition, where it says: "The 'readymades' are among the most influential of Duchamp's works. They are ordinary objects that anyone could have purchased at a hardware store [...]. The first readymade, however, done in 1913 by fastening a bicycle wheel to a stool, was "assisted" by Duchamp, and hence is an assemblage on the part of the discoverer as well as the original manufacturer." (Catalogue The Museum of Modern Art, New York: The Art of Assemblage. 2 October - 12 November 1961 (ed. by William C. Seitz) New York: The Museum of Modern Art and Doubleday, 1961, p. 46. 9. Marvin Lazarus, quoted from Gough-Cooper, Jennifer; Caumont, Jacques: Ephemerides on and about Marcel Duchamp and Rrose Sélavy 1887-1968. London: Thames and Hudson, 1993, no page number (entry for 11 November 1961). 10. Pontus Hulten in a letter to the author, 26 July 2000. A contemporary review in a newspaper from 17 March 1961 gives another hint. There it says: "Nu geef je tegen het wiel een zetje. Wat gebeurt? Ja, precies - het wiel gaat draanien." (English translation: "Now one touches the wheel. What happens? Yes, precisely - the wheel starts turning.", quoted from anon.: In A'dams museum beleeft men: De nachtmerrie van een fietsenmaker. In: Overijsselse en zwolsche Courant, 17 March 1961, no page number, with regards to Dr. Maurice Rummens, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam). 11. Pontus Hulten in a letter to the author, 26 July 2000. 12. This replica was signed by the artist when Duchamp visited Stockholm in late August, early September 1961. Today it belongs to the Moderna Museet, Stockholm. 13. see i.a. catalogue Museum Ludwig, Cologne: Robert Rauschenberg - Retrospektive. 27 June - 11 October 1998 [ed. by Walter Hopps and Susan Davidson]. Ostfildern-Ruit: Cantz, 1998, p. 560. 14. see George Brecht in catalogue Kunsthalle Bern: Jenseits von Ereignissen: Texte zu einer Heterospektive von George Brecht. 19 August - 24 September [ed. Marianne Schmidt-Miescher; Johannes Gachnang]. Bern: Kunsthalle, 1978, p. 94. 15. see Virginia Dwan in Stuckey, Charles F.: Interview with Virginia Dwan conducted by Charles F. Stuckey, 21 March 1984, The Oral History Collections of the Archives of American Art, New York Study Center, p. 8. 16. "Peut-on faire des oeuvres qui ne soient pas d'art?" says the 1913 facsimile note in the box à l'infintif, 1967.

|

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου