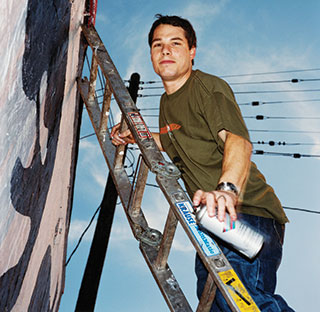

Artist Shepard Fairey cut his teeth on the mean streets of Los Angeles, so he’s definitely not going to let some pipsqueak organization called the Associated Press push him around.

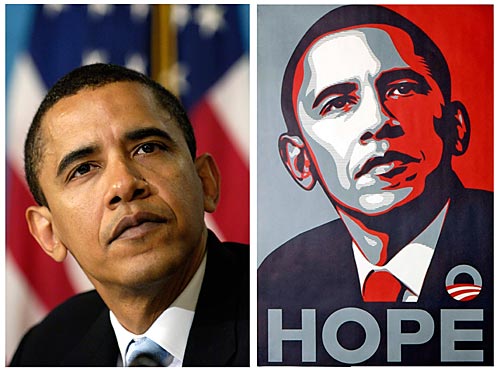

This week, Fairey responded to a lawsuit filed by the AP in which the news organization claims that the artist broke copyright laws when he used its photograph of Barack Obama for his “Hope” poster.

Fairey’s lawyers said in papers filed at a New York court Wednesday that the artist’s use of the photograph is protected by the First Amendment as well as by fair-use laws.

But the real attention-grabber was Fairey’s assertion that the AP itself violated copyright laws when it used a photo of the artist’s “Hope” poster without getting permission. In other words, he’s arguing that the AP can’t reproduce an image by Fairey that the artist himself appropriated from the AP.

Did we just fall into a rabbit hole? Here’s what Fairey’s lawyers wrote:

“On January 7, 2009 The AP distributed a story entitled ‘Iconic Obama portrait headed to Smithsonian museum’ by Brett Zongker. The AP’s article included a photograph attributed to The AP, which depicted Fairey’s Obama Hope Stencil Collage that now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution…. The AP did not obtain a license to use Fairey’s work in this photograph. As shown below, the photograph attributed to The AP consists of nothing more than a literal reproduction of Fairey’s work.”

They also accuse the AP of similarly infringing the copyright on works by Jeff Koons, Banksy Keith Haring and George Segal.

We at Culture Monster know that L.A. art-hipsters can be a pretty sarcastic and smart-alecky group of people. (Call it a permanent state of ironic detachment.) Whether Fairey is merely thumbing his nose at the venerated news institution or if these new claims have real merit — or both! — remains to be seen.

However you look at it, this saga is long from over. Check back often, folks.

David Ng

Los Angeles Times

Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe

Memorials are unusual structures. In a post-modern world of fractured meanings, these structures still attempt (and largely succeed) to present a clear, unified and highly-subjective view on world events. Some memorials, though, defy straightforward interpretation.

One example is the massive holocaust memorial in Berlin — “Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe” — which has been the cause of much controversy over the past decade for failing to acknowledge the non-Jewish victims of the Nazis and, as part of Germany’s “Holocaust industry”, exploiting the country’s sense of shame and disgrace.

But as I walked through the memorial — which consists of more than 2,700 stone pillars built onto an undulating 4.7 acre plot close to the Brandenburg Gate and was designed by architect Peter Eisenman — it occured to me that this memorial is much more open to interpretation than most other stone-built momento moris.

For one thing, it’s very experiential and interactive. You don’t just look at it. You get inside it. In parts of the memorial, I felt very removed from the sky, like I was in a cave. I felt like I was descending into a labyrinthian dungeon. In other parts, I could perch on a stone pillar, see for miles and feel the warm air around me. At times, I felt very solitary and alone. At others, I felt like I was in a crowd. The pillars seemed like people. Every turn I made, I came across fellow memorial wanderers. I even saw a young couple necking in a shady enclave.

Nowhere inside the memorial or around it, does it say what it commemorates. Which leads me to think that while the structure has been built to commemorate a particular event, it means so much more. It can stand for a place of mourning and a hideaway for a surreptitious tryst.

What does it mean to me? It means death and life both at once. It means getting lost and finding oneself again. Despite the title of the memorial, its Jewishness feel abstract to me, probably because I grew up many decades after the close of the war in a family that, though Jewish, is essentially secular. The intention behind the creation of a memorial is an important consideration. It’s difficult to experience the structure without a thought for the murdered Jews that it seeks to honor. But ultimately, its meaning is as much of a maze as the narrow corridors that greet the explorer as she approaches the structure.

Chloe Veltman

Lies Like Truth

The RAND report — which is truly worth the detour — is first and foremost a literature review. Its authors have painstakingly trawled through the vast and scattered sources that address why cultural activity is — or more accurately may possibly be — of value; classified that literature (economic, social, psychological, aesthetic etc.); and then sought to give a broad account of how robust are the conclusions of the various studies.

They conclude, as others have before them, but never with such crushing evidential force, that the recent literature is a bit flaky, and that the wilder claims for the social and economic impact of the arts are overblown. This is not surprising. Much of the literature was generated in the context of the ruthless pursuit of money rather than the fearless pursuit of truth. Its purpose is not to increase the sum of human understanding but to persuade particular constituencies (usually public sector funders) in particular contexts (a capital project, a fiscal crisis) to maintain or increase levels of financial support.

I doubt many of the authors cited thought they were carrying responsibility for the intellectual underpinning of the Enlightenment. Their job was to play on the sensibilities of a particular group of decision makers. The arts constituency has been extremely successful in raiding the budgets of adjacent and better funded policy areas – education, urban renewal, tourism etc…

Some of the instrumental arguments are obviously a bit of stretch. Others are obviously true. But the arcane and (pace RAND) flawed methodologies employed rarely generate conclusions that are not accessed more easily, convincingly and cheaply by the application of common sense.

The overall ‘impact’ of the instrumental enterprise has been to leave the sector over-hyped, over-extended and cowering as it waits to be found out. Hence the reaction within the sector to the RAND report – “So whose side are you guys on then?” I got the same reaction to the debate on the same issues that we got going in the UK in 2003 and referenced in the right-hand sidebar to this blog. My perspective, like Midori’s, was that it’s not ‘either instrumental or intrinsic’ but that there are a wide range of arguments that apply differentially to a wide range of cultural activities and seeking to fit the whole of cultural endeavor into a single straight-jacket is both uncomfortable and unhelpful.

The current preoccupation with re-grounding the arguments for the public support of cultural activity is a result of this gut-churning awareness by the arts policy community that the hard-won gains in arts funding have been, in large part, as a result of aggressive but shakily-grounded lobbying. The re-grounding, heralded by the RAND authors and others like John Holden, as and when it happens – incrementally, awkwardly, partially — will bring with it not only changes in the gross level of arts funding but changes in the type of organizations and activities funded. This is no bad thing and indeed rather exciting.

My gripe with the current preoccupation with this vast literature and its methodological shortcomings is that it is something of a side show. This is not primarily because, as the RAND report demonstrates, the re-grounding of economic and social arguments in more analytically defensible research methodologies would take a long time and cost a lot of money that could be better spent elsewhere – though this is undoubtedly the case. It is primarily because the cultural sector seems to feel the need to hold itself to higher (or maybe just odder) evidential standards than other sectors – for example, health, environment, or education. In these sectors, the academic preoccupation is not with, for example, what health can do for urban regeneration or tourism, but with the policies required to ensure a healthy community.

If we stopped looking so neurotically for epiphenomena — the impact of the arts on X, Y and Z — and diverted our attention to what constitutes — say — a vibrant cultural community: what distribution of what art forms, what forms of participation etc. — and if we could come up with well grounded answers to this question, I suspect that those answers would be significantly more compelling to the decision-makers we lobby than another damned economic impact study. We would spend less time waiting for the other shoe to drop as decision makers discover what we already knew and what the RAND report has spelled out in merciless detail. And we would address some of the patently daft misallocations of scarce resources that our shakily-grounded arguments for the arts have encouraged, such as the resource-draining building boom we are emerging from, which has left the sector over-expanded, under-capitalized and with a fundamentally and adversely altered ratio of fixed to variable costs.

Adrian Ellis

Arts Journal

One might argue that commercial success is not the same thing as artistic success, but Warhol taught us that things can be otherwise. Business art was the ultimate validation of one’s aesthetic skills. If people bothered to buy an artist’s work then by extension one could conclude that the artist was producing good art. These days, the intimate relationship between money and successful art means that really good art sells. And maybe some good art doesn’t sell, but when the bohemian art demigod Ryan McGinley gets hired to do photography for the New York Times and has an entire project devoted to documenting Kate Moss, one might say that the economic market validated what the art world already knew: McGinley is an art superstar. His commercial success is merely a signal of his brilliance. Art goers can bicker endlessly about whether commercial art validates or detracts from the virtue of an artist, but ultimately this is an existential debate: The reality is that given the opportunity to make a living out of making art, many artists will choose to do so and there’s really nothing wrong with that.

When I interviewed Shepard Fairey several months ago for the research I conduct, he (like the other artists I spoke with) bore no ill will toward either the masses or the elite art world. He just wanted to do what he loved to do, and he was happy that it had been a successful venture that allowed him to provide an income for himself and own his own company. He also told me that it was important that he was able to get his art out there to as many people as possible. As he put it, “I can make pieces that are expensive but I want to sell $35 screen prints and $25 T-shirts. Where I am coming from in my work is that art is empowering. I want people to be able to access me…I never started as a fine artist and felt like a ’sell out’. I went in the opposite direction. I really like the street artist – you didn’t have to submit to a gallery or a magazine, you just went out and did it…A T-shirt is a walking piece of art. When I do a record label’s album cover, I am producing art that gives people pleasure while listening.”

Elizabeth Currid

Gawker

Many bloggers are spinning out the story of Brandeis University and its imperiled Rose Art Museum… In a nutshell, the university is desperately strapped for cash, and inelegantly floated the idea of ”repurposing” the art and assets of the Rose to balance the books.

I’ll let others explore and explain the complexities of deaccessioning/selling works of art — a juicy issue on its own. I’m struck, instead, by the related question of mission, process, and ”ownership” in the work of embedded institutions.

If you were to do a genuine census of arts venues and programs — performing and visual — you would find a good percentage of those were ”embedded” enterprises. Rather than separate nonprofits, these would be venues and programs completely contained within larger (generally nonprofit, predominantly higher education) institutions. The university presenter or museum, for example, may well have an independent advisory board that looks like a board of trustees. But often their actual authority to define mission and allocate resources is hazy, split, or complex.

Therein lies both the benefit and the rub:

Life as an embedded institution has benefits: You have access to a diversified parent institution that can help with cash flow, business services, purchasing, maintenance, and other central services. Many of the traditional expenses of a separate nonprofit are handled ”off book” as part of the larger enterprise. And many of your salary lines may be shared with other departments, programs, or functions.

But there’s a downside, as well. It can be a challenge to know exactly what gains you gather and what costs you incur, since your work is done through a hundred different channels and accounts. And, at the end of the day, you are a sub-contractor for someone else’s mission. When resources get tight, and the parent institution gets hungry, your programming and even your existence could become subject to increasing scrutiny.

Says Felix Simon in this rather gruesome discussion of the Brandeis and the Rose:

Up until now, we’ve lived in a world where parents implicitly promise to support their children, and not to murder them or amputate key limbs. But now that Brandeis and Iowa are starting to eat their own, the topology has changed in a radical way.

Precisely because parents like Brandeis have an obligation to do what they think is best for the university, they can no longer be trusted to do what is best for the museum.

Over the past many years, the arts industries have come to rely on embedded institutions to bear more of the risk required of a healthy ecosystem. University presenters are among the few remaining commissioners of new work. University cultural institutions have taken the lead in artist residencies and exploration. And a dual mission can make them ideal ”farm league” for young artists, technicians, and support personnel.

The Rose reminds us that risk-aversion and bottom-line analysis are alive and well in higher education, and will be a growing threat to those cultural organizations who live and die as subsidiaries to a larger corporation.

Andrew Taylor

The Artful Manager

From skateboarder to famous street artist, Shepard Fairey has seen the inside of numerous police cells in his long career. This week his ubiquitous portrait of Barack Obama, which appeared on billboards, T-shirts, hats and magazine covers throughout the 2008 election season, was acquired by the National Portrait Gallery in Washington.

Until he came up with his Obama image and went on to be named “Icon Maker” of the year by Time magazine, 38-year-old Fairey was best known for his rock-music album covers and an advertising campaign that featured a wrestler named Andre the Giant.

The artist’s most recent arrest was last August when he was in Denver for Mr Obama’s nomination to stand as the Democratic presidential candidate. He was busy postering an alleyway with some friends while a film crew documented their work, when riot police showed up. Fairey, who is diabetic, recalls how he and his fellow street artists dropped their posters, brushes and buckets of paste and legged it down the alley, only to be confronted by five paramilitary-style police pointing guns at their heads.

“I guess we got too close to the hot zone down town,” Fairey recalled as he waved a pretend gun in imitation of the cops: “Get on the ground or we’re gonna kick you in the head … We were quickly zip-tied and taken off to jail.” He spent the night in a cell with some anarchists and was fed the favourite snack of all American teenagers: “peanut and jelly sandwiches”.

Fairey graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design and went on to found a design studio which specialised in “guerrilla marketing”.

While Mr Obama was accepting the Democratic nomination, Fairey, out of jail with a slap on the wrist, was already filming a YouTube account of the 14th arrest in his meteoric career as America’s foremost street artist.

The story of his famous Obama portrait, a large-scale, mixed-media stencilled collage, is already taking on the mythic qualities of a quintessential American narrative. Emerging from humble beginnings in the back alleys of Los Angeles, the portrait became an instant sensation, a pop culture “icon” that was willingly embraced by the Obama political machine.

Before the President-elect swears his oath of office on Abraham Lincoln’s personal Bible, the portrait has become part of the Smithsonian’s permanent collection at the National Portrait Gallery, which is conveniently only a few blocks from the White House. Fittingly for the narrative of change, the Obama portrait was donated to the gallery by the head of Mr Obama’s transition team, Tony Podesta, and his wife, Heather.

The striking resemblance to the Che Guevara portrait which has decorated generations of student bed-sits, has not been dwelt on. But a little way from where Fairey’s portrait will hang there is a small portrait of the Cuban revolutionary by Charles “Chaco” Chavez, drawn from the famous photograph by Alberto Korda.

The portrait gallery is better known for its stuffy collection of George Washington portraits than street art, but the museum’s curator, Carolyn Kinder Carr, said simply: “We all fell in love with it. We always like portraits that reflect a particular moment in history, and we like the fact that it is an image that resides in popular culture.”

It’s not the first time that street art has been brought in from the cold, she noted: “The posters of [Henri de] Toulouse-Lautrec are essentially street art.” And there seem to be few bounds to Fairey’s capacity for self publicity. This week, for example, it was announced that he has donated a new image to Adopt-a-Pet.com, to promote the cause of rescuing street mutts. Mr Obama is hoping to adopt a pet from a shelter for the White House.

Fairey explained that he is “a big believer in speaking up for all who suffer injustice, regardless of gender, race, sexual orientation or, in this case, species!” He created a limited-edition run of 400 signed and numbered silk-screen prints in honour of a dog he had as a child growing up in Charleston, South Carolina, a mutt named Honey.

At the portrait gallery, meanwhile, the director, Martin E Sullivan, intoned: “This work is an emblem of a significant election, as well as a new presidency. Shepard Fairey’s instantly recognisable image was integral to the Obama campaign.”

Fairey’s collage became the central portrait image for the Obama campaign and was initially distributed as a limited-edition print and then as a free download. His other works are in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The new portrait will be hanging at the gallery by 17 January, three days before Mr Obama’s inauguration. Suitably enough it will be in the “New Arrivals” section on the ground floor.

Leonard Doyle

The Independent

During the first half of the twentieth century—decades of war and revolution—an “intellectual migration” relocated thousands of artists and thinkers to the United States, including some of Europe’s supreme actors, dancers, composers, and filmmakers. For them, America proved to be both a strange and opportune destination. A “foreign homeland” (Thomas Mann), it would frustrate and confuse, yet afford a clarity of understanding unencumbered by native habit and bias. However inadvertently, the condition of cultural exile would promote acute inquiries into the American experience. What impact did these famous newcomers have on American culture, and how did America affect them?

Exploring these questions in my book Artists in Exile, I found that, taken as a whole, twentieth-century American immigrants in the performing arts were not able to sustain a full growth curve upon relocating. Some lost their way entirely. Of those who did not, almost all enjoyed a more consummated European calling. The exceptions—the major old-world careers that accelerated in the New World—can be counted on the fingers of one hand: George Balanchine in dance, Americanizing classical ballet; Ernst Lubitsch in film, parlaying operetta wit into a prized Hollywood confection; the pianist Rudolf Serkin, a heroic American solo artist and relentless American pedagogue; the conductor Serge Koussevitzky, whose Tanglewood Festival became a New England laboratory for new American music. More typically, unreplantable old-world roots signified stunted cumulative growth. And yet, in every field the intellectual migration raised the bar; the arena was enlarged.

The final stirrings of cultural exchange in American exile—a postscript to my account—are to be found among post-Stalin defectors from the Soviet Union and its satellites. The most significant American-based careers include those of Milos Forman and Mikhail Baryshnikov. In Forman’s superb Hollywood production, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), the droll, affectionate, and painstaking observation of human behavior, typical of his Czech films, is applied to the inmates of an American insane asylum and so powers a reading of psychological subjugation informed by the director’s own experience of confinement and debasement in Communist Czechoslovakia. Baryshnikov escaped the Kirov’s Soviet traditionalism to work with a gamut of American choreographers—Alvin Ailey, Balanchine, Eliot Feld, Mark Morris, Jerome Robbins, Twyla Tharp—in addition to joining Natalia Makarova and Rudolf Nureyev in impressing the full-length Russian ballet classics upon American audiences.

Joseph Horowitz

Humanities

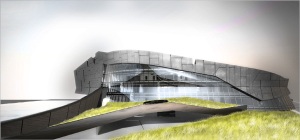

Thom Mayne’s design for a corporate headquarters in Shanghai. (Courtesy of Morphosis)

Four months ago the architect Daniel Libeskind declared publicly that architects should think long and hard before working in China, adding, “I won’t work for totalitarian regimes.” His remarks raised hackles in his profession, with some architects accusing him of hypocrisy because his own firm had recently broken ground on a project in Hong Kong.

Since then, however, Mr. Libeskind’s speech, delivered at a real estate and planning event in Belfast, Northern Ireland, has reanimated a decades-old debate among architects over the ethics of working in countries with repressive leaders or shaky records on human rights.

With a growing number of prominent architects designing buildings in places like China, Iran, Abu Dhabi and Dubai, where development has exploded as civic freedoms or exploitation of migrant labor have come under greater scrutiny, the issue has inched back into the spotlight.

Debate abounds on architecture blogs, and human rights groups are pressing architects to be mindful of a government’s politics and labor conditions in accepting commissions.

The ideological issue is as old as architecture itself. By designing high-profile buildings that bolster the profile of a powerful client, do architects implicitly sanction the client’s actions or collaborate in symbolic mythmaking?

Or in the long run does architecture transcend politics and ideology? If the architect’s own vision is progressive, can architecture be a vehicle for positive change?

For the most part, the issue is not a concrete one for the field’s top practitioners; no architect interviewed for this article except Mr. Libeskind has publicly rejected the notion of working for hot-button countries. Yet the debate underscores the complex decisions that go into designing architecture — from the basic financial imperatives, to public access, to the larger message that a building sends — and is prodding architects to reflect on their priorities.

“It’s complicated,” said Thom Mayne, the Los Angeles architect, whose projects include a corporate headquarters in Shanghai. “Architecture is a negotiated art and it’s highly political, and if you want to make buildings there is diplomacy required.”

“I’ve always been interested in an architecture of resistance — architecture that has some power over the way we live,” added Mr. Mayne, who said he had recently been interviewed for projects in Abu Dhabi, Kazakhstan, Russia, the Middle East and Indonesia. “Working under adversarial conditions could be seen as a plus because you’re offering alternatives. Still there are situations that make you ask the questions: ‘Do I want to be a part of this?’ “…

Some architects argue that architecture is more important to them than politics. “I’m a guy who has on my wall a picture of the guy in front of the tank,” said Eric Owen Moss, a Los Angeles architect, referring to the famous photograph from the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. “But I’ve never turned down a project in Russia and China”…

Architects like Steven Holl cast their decision to build in China as a way of promoting a connection between East and West. “Certainly I question working anywhere,” Mr. Holl said. “But my position as an architect is to work in the spirit of international civilization and cooperation. You have to make a contribution.”

He cited his two-million-square-foot Linked Hybrid housing complex in Beijing, which will be heated and cooled by a 660-well geothermal energy system. “We are making the largest green total community in the history of Beijing,” Mr. Holl said. “This is an example for many kinds of urban work.”

Others go even further, arguing that their projects will be an emphatic force for social change. The Swiss architect Jacques Herzog has asserted that by supplying acres of public park space to city dwellers in the long term, his Olympic stadium in Beijing, designed with his partner, Pierre de Meuron, “will change radically — transform — the society.”

“Engagement is the best way of moving in the right direction,” he said.

Robin Pogrebin

New York Times

The Dia Art Foundation is hoping to raise $1.1m by the end of next month to protect 6,000 acres of land surrounding Walter De Maria’s land art installation Lightning Field.

The money will be used to pay a ranching family in western New Mexico, who own the land, for the right to restrict real estate and industrial development. This would create a three-mile radius around the installation. The restrictions on the property will bind all future landowners and become part of the chain of title for the estate.

According to Laura Raicovich, deputy director at the foundation: “The experience of Lightning Field depends upon the isolation of the site, and we’d like to preserve the setting for future generations.” She says the organisation has raised $900,000 to date, including $500,000 committed by the State of New Mexico, and says she is confident they will reach their goal by the official deadline in June.

Commissioned and maintained by the Dia, De Maria’s land sculpture consists of 400 polished stainless steel poles installed in a rectangular grid measuring 1.6km by 1km. The work is situated in an unpopulated area about four hours outside of Albuquerque, and is designed for viewers to observe the effects of meteorological phenomena on the installation over time. Visitation is strictly monitored to only six people per day, and reservations must be made months in advance through written correspondence. Since Lightning Field was completed in 1977, nearly 13,000 visitors have visited the site.

The Dia is currently in the midst of another preservation campaign for a land art installation in their permanent collection, Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty. The State of Utah will decide this month whether to permit oil drilling near the site.

Filling the boards of arts companies with business appointees has been a dismal failure that has stifled creativity.

That is the view of the international arts entrepreneur Justin Macdonnell, who wants a radical rethink of the way arts companies are run.

For too long arts companies had been urged by funding bodies to simulate the business sector, he said yesterday at the first in a series of breakfast forums, Arts And Public Life, held by the arts organisation Currency House.

“Who has not been told that they need to get more people with ‘business skills’ on their board, more people with financial, legal, marketing prowess to guide and restrain the wilful artist – as though it were the arts that regularly had the corporate crashes, bankruptcies and shady dealings?” Macdonnell said.

This move had restricted the ability of arts boards to make informed judgments. Ironically, the funding agencies that had pushed their clients in that direction were now questioning whether the boards had the capacity to choose good artistic leadership.

“Throughout the English-speaking world, the board system of governance in the not-for-profit sector has been a miserable failure,” he said.

Macdonnell, who returned to Australia this year to establish the Anzarts Institute as an advocate for the arts, told the Herald credentials for appointing board members were often questionable.

“The pendulum has swung so far in the direction of appointing people to arts boards whose primary skill is to be business people and who are appointed on the grounds that maybe they’ve been a subscriber or an audience member or they’re described as a lover of the arts,” he said.

“Well, I’m a subscriber to Telstra but that doesn’t mean anyone would put me on [its] board or put me in charge of communications policy.”

Macdonnell, who has spent the past five years in Miami as artistic director of the Carnival Centre for the Performing Arts and who has worked extensively in South America, said the appointment of board members was taken seriously in the US. Potential board members received guidance there.

But he did not believe that simply including more artists on boards was a solution. What was needed was a way for artists and their boards to work more collaboratively and a rethink of the way arts companies were structured.

“Are we so limited in our thinking that we can come up with no better way of doing business than a company limited by guarantee with a board of seven and an uneasy diarchy of general manager and artistic director?” he said.

Many art forms around the world were in crisis, particularly classical music, which had raised the worship of the past to cult status. Theatre companies seemed to be in better shape because they were presenting current work as well as past.

“But they, too, seem to rely more on celebrity than substance in their quest for renewal,” Macdonnell said.

His five years in Miami had taught him that arts organisations had few skills in fostering and managing innovation.

Arts centres in the US were essentially presenters, not creators, of work.

“They take their shopping cart to the arts mall – also known as the booking conference – and buy pre-packaged shows off the shelf, like frozen peas,” he said.

“And they thaw them out for touring. To me, however, a presenter ought to present not just the pre-packaged but the fresh food as well – work made by our own artists.”

Joyce Morgan

Sydney Morning Herald