Art, Publishing, and Crisis

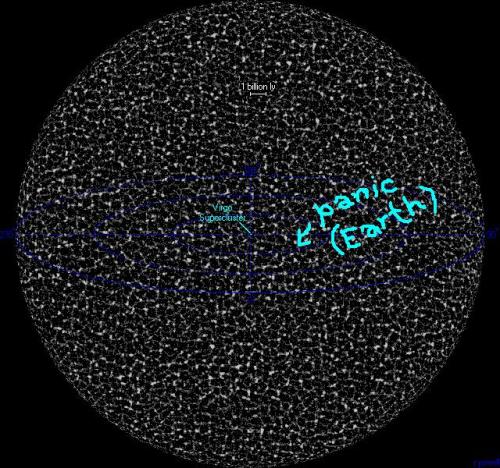

We picked an interesting year in which to start writing about publishing and art, since as even a casual observer knows by now, the clouds are darkening above both industries. From the daily death march of publishing headlines on Gawker and GalleyCat—layoffs! breakups! breakdowns!—to the recent New York article asking “Who Will Bail Out the Publishers?”, signs of crisis are everywhere, prompting tough, even existential questions about the future of books. Meanwhile, this month’s issue of Prospect magazine warns that the bottom is about to fall out of the contemporary art market in what they call a repeat of the 17th-century Holland tulip craze. Needless to say, both of these crises have potentially severe implications for another of this site’s main subjects: New York City, which is already reeling from its recent financial meltdown (the wellspring of all this trouble, naturally) and which now finds its cherished primacy as an art and literary mecca under threat. And how is the Universe doing these days?

On the whole, not too bad, actually.

It’s time to take a step back—way back. (Abbeville occupies a small and specialized niche, so we don’t have the industry-wide perspective that GalleyCat and Gawker provide; and of course our relationship to the art industry is only tangential. As always on this site, we speak purely as book lovers, art lovers, and would-be opinionators.) The times are indeed grim, and our sympathy for those who are losing their jobs or struggling to sell their creative work—particularly during the holiday season—is heartfelt. Everybody is feeling the pinch and it’s no fun at all. At the same time, we resist hysterical prophecies of doom as instinctively as we do the kind of reckless optimism that inflates bubbles, causes industries to overexpand, and creates these messes in the first place. The cure for both syndromes, sententious as it may sound, is a renewed focus on things of permanent value.

In the case of the contemporary art market, the danger of a crash—which is very real—should have been obvious to anyone paying attention for the past several years. Reputations and prices were absurdly overinflated; financial shell games were played; quality was often disregarded altogether. It’s hard not to shrug and repeat the old saying about a fool and his money, but of course the problem isn’t just cunning auction houses or gullible collectors. Too many artists for too many years have been playing variations on Piero Manzoni’s Merda d’artista, or, if you like, on the pranks of the Dadaists (though these at least were original)—trafficking in grade-school ironies and an utter contempt for their audience…

Meanwhile, of course, there’s Art.

It can’t be mass-produced, it isn’t fashionable, it’s hard to make a killing on because it’s mostly owned by big institutions already, but it does have a way of reducing contemporary, big-business art and all its troubles to a small, far-off noise. And it’s there to study for anyone who would rather try to discover—or create—its equivalent, and profit from it years from now if at all, than make a quick buck on trashy substitutes.

As for our own industry, we would modestly propose that publishers attempt a similar investment in lasting quality instead of chasing down the newest ghostwritten celebrity tome or the latest popular “literary” craze. Some have claimed that it’s necessary to sell loads of chaff in order to be able to carry the wheat at all, but this is an old and fallacious argument (not least because half the time, the chaff doesn’t sell either). In books as on the Internet, “content is king,” and the world will never lack for terrific content languishing in obscurity. Recognizing it is difficult; supporting it is risky; but making a concerted effort to do both offers publishers the best chance for survival in the end. As GalleyCat put it recently:

“Even though independent publishers are themselves not immune to the economic pressures, many are prepared to press on and carve out a unique space for themselves because they don’t want to live in a world where the books they love aren’t available for others to read. They may press on cautiously, and slowly, and they may not gain huge ground most years, but they will persevere, as will their equally passionate counterparts at the larger houses, because they must.”

Bravissimo. Compare to this Oscar Wilde’s lament that ”in the old days books were written by authors and read by the public. Nowadays books are written by the public and read by nobody.” Over a century later, this comic exaggeration threatens to become literal as books compete for attention with innumerable other media outlets. Only a return to books and artworks that their creators and vendors love will ensure an audience that continues to love them, and buy them, as well.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου