Fernand Léger

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Joseph Fernand Henri Léger (February 4, 1881 – August 17, 1955) was a French painter, sculptor, and filmmaker.

Contents[hide] |

Biography

Léger was born in the Argentan, Orne, Basse-Normandie, where his father raised cattle. Fernand Leger initially trained as an architect from 1897-1899 before moving in 1900 to Paris, where he supported himself as an architectural draftsman. After military service in Versailles in 1902-1903, he enrolled at the School of Decorative Arts; he also applied to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts but was rejected. He nevertheless attended the Beaux-Arts as a non-enrolled student, spending what he described as "three empty and useless years" studying with Gérôme and others, while also studying at the Académie Julian.[1] He began to work seriously as a painter only at the age of 25. At this point his work showed the influence of Impressionism, as seen in Le Jardin de ma mère (My Mother's Garden) of 1905, one of the few paintings from this period that he did not later destroy. A new emphasis on drawing and geometry appeared in Léger's work after he saw the Cézanne retrospective at the Salon d'Automne in 1907.[2]

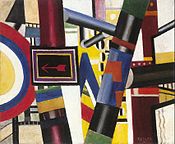

In 1909 he moved to Montparnasse and met such leaders of the avant-garde as Archipenko, Lipchitz, Chagall, and Robert Delaunay. His major painting of this period is Nudes in the Forest (1909-10), in which Léger displayed a personal form of Cubism—his critics called it "Tubism" for its emphasis on cylindrical forms—that made no use of the collage technique pioneered by Braque and Picasso.[3]

In 1910 he joined with several other artists, including Delaunay, Jacques Villon, Henri Le Fauconnier, Albert Gleizes, Francis Picabia, and Marie Laurencin to form an offshoot of the Cubist movement, the Puteaux Group—also called the Section d'Or (The Golden Section). Léger was influenced during this time by Italian Futurism, and his paintings, from then until 1914, became increasingly abstract. Their vocabulary of tubular, conical, and cubed forms are laconically rendered in rough patches of primary colours plus green, black and white, as seen in the series of paintings with the title Contrasting Forms.

Léger's experiences in World War I had a significant effect on his work. Mobilized in August 1914 for service in the French Army, he spent two years at the front in Argonne. He produced many sketches of cannons, airplanes, and fellow soldiers while in the trenches, and painted Soldier with a Pipe (1916) while on furlough. In September 1916 he almost died after a mustard gas attack by the German troops at Verdun. During a period of convalescence in Villepinte he painted The Card Players (1917), a canvas whose robot-like, monstrous figures reflect the ambivalence of his experience of war. As he explained:

...I was stunned by the sight of the breech of a 75 millimeter in the sunlight. It was the magic of light on the white metal. That's all it took for me to forget the abstract art of 1912-1913. The crudeness, variety, humor, and downright perfection of certain men around me, their precise sense of utilitarian reality and its application in the midst of the life-and-death drama we were in...made me want to paint in slang with all its color and mobility.[4]

This painting marked the beginning of his "mechanical period", during which the figures and objects he created were characterized by sleekly rendered tubular and machine-like forms. Starting in 1918, he also produced the first paintings in the Disk series, in which disks suggestive of traffic lights figure prominently.[5] In December 1919 he married Jeanne-Augustine Lohy, and in 1920 he met Le Corbusier, who would remain a lifelong friend.

The "mechanical" works Léger painted in the 1920s, in their formal clarity as well as in their subject matter—the mother and child, the female nude, figures in an ordered landscape—are typical of the postwar "return to order" in the arts, and link him to the tradition of French figurative painting represented by Poussin and Corot.[6] In his paysages animés (animated landscapes) of 1921, figures and animals exist harmoniously in landscapes made up of streamlined forms. The frontal compositions, firm contours, and smoothly blended colors of these paintings frequently recall the works of Henri Rousseau, an artist Léger greatly admired and whom he had met in 1909.

They also share traits with the work of Le Corbusier and Amédée Ozenfant who together had founded Purism, a style intended as a rational, mathematically based corrective to the impulsiveness of cubism. Combining the classical with the modern, Léger's Nude on a Red Background (1927) depicts a monumental, expressionless woman, machinelike in form and color. His still life compositions from this period are dominated by stable, interlocking rectangular formations in vertical and horizontal orientation. The Siphon of 1924, a still life based on an advertisement in the popular press for the aperitif Campari, represents the high-water mark of the Purist aesthetic in Léger's work.[7] Its balanced composition and fluted shapes suggestive of classical columns are brought together with a quasi-cinematic close-up of a hand holding a bottle.

As an enthusiast of the modern, Léger was greatly attracted to cinema, and for a time he considered giving up painting for filmmaking.[8] In 1923-24 he designed the set for the laboratory scene in Marcel L'Herbier's L'Inhumaine (The Inhuman One). In 1924, in collaboration with Dudley Murphy, George Antheil, and Man Ray, Léger produced and directed the iconic and Futurism-influenced film, Ballet Mécanique (Mechanical Ballet). Neither abstract nor narrative, it is a series of images of a woman's lips and teeth, close-up shots of ordinary objects, and repeated images of human activities and machines in rhythmic movement.[9]

In collaboration with Amédée Ozenfant he established a free school where he taught from 1924, with Alexandra Exter and Marie Laurencin. He produced the first of his "mural paintings", influenced by Le Corbusier's theories, in 1925. Intended to be incorporated into polychrome architecture, they are among his most abstract paintings, featuring flat areas of color that appear to advance or recede.[10]

Starting in 1927, the character of Léger's work gradually changed as organic and irregular forms assumed greater importance.[11] The figural style that emerged in the 1930s is fully displayed in the Two Sisters of 1935, and in several versions of Adam and Eve.[12] With characteristic humor, he portrayed Adam in a striped bathing suit, or sporting a tattoo. In 1935, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City presented an exhibition of his work.

During World War II Léger lived in the United States, where he found inspiration in the novel sight of industrial refuse in the landscape. The shock of juxtaposed natural forms and mechanical elements, the "tons of abandoned machines with flowers cropping up from within, and birds perching on top of them" exemplified what he called the "law of contrast".[13] His enthusiasm for such contrasts resulted in such works as The Tree in the Ladder of 1943-44, and Romantic Landscape of 1946. A major work of 1944, Three Musicians (Museum of Modern Art, New York), reprises a composition of 1930. A folk-like composition reminiscent of Rousseau, it exploits the law of contrasts in its realistic juxtaposition of the three men and their instruments.

Upon his return to France in 1945, he joined the Communist Party. During this period his work became less abstract, and he produced many monumental figure compositions depicting scenes of popular life featuring acrobats, builders, divers, and country outings. Charlotta Kotik has pointed out that Leger's "determination to depict the common man, as well as to create for him, was a result of socialist theories widespread among the avant-garde both before and after World War II. However, Léger's social conscience was not that of a fierce Marxist, but of a passionate humanist[.]"[14] His varied projects included book illustrations, murals, stained-glass windows, mosaics, polychrome ceramic sculptures, and set and costume designs.

After the death of his wife in 1950, Léger married Nadia Khodossevitch in 1952. In his final years he lectured in Bern, designed mosaics and stained-glass windows for the Central University of Venezuela in Caracas, Venezuela, and painted Country Outing, The Camper, and the series The Big Parade. In 1954 he began a project for a mosaic for the São Paulo Opera, which he would not live to finish. Fernand Léger died at his home in 1955 and is buried in Gif-sur-Yvette, Essonne.

Léger wrote in 1945 that "the object in modern painting must become the main character and overthrow the subject. If, in turn, the human form becomes an object, it can considerably liberate possibilities for the modern artist." As he explained in a 1949 essay, by allowing the object to replace the subject, "we were able to consider the human figure as a plastic value, not as a sentimental value. That is why the human figure has remained willfully inexpressive throughout the evolution of my work".[15] As the first painter to take as his idiom the imagery of the machine age, and to make the objects of consumer society the subjects of his paintings, Léger has been called a progenitor of Pop Art.[16]

He was active as a teacher for many years. Among his pupils were Robert Colescott, Hananiah Harari, Asger Jorn, Beverly Pepper, George L. K. Morris, and Charlotte Gilbertson.

In 1952, a pair of Léger murals was installed in the General Assembly Hall of the United Nations headquarters in New York, New York.

In 1960, the Musée Fernand Léger was opened in Biot, Alpes-Maritimes,France.

In November of 2003, his painting, La femme en rouge et vert sold for 22,407,500 United States dollars. His sculptures have been selling in excess of 8 million dollars.

- Buck, Robert T. et al. (1982). Fernand Léger. New York: Abbeville Publishers. ISBN 0-89659-254-5

- Cowling, Elizabeth; Mundy, Jennifer (1990). On Classic Ground: Picasso, Léger, de Chirico and the New Classicism 1910-1930. London: Tate Gallery. ISBN 1-854-37043-X

- Eliel, Carol S. et al. (2001). L'Esprit Nouveau: Purism in Paris, 1918-1925. New York: Harry Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0-8109-6727-8

- Néret, Gilles (1993). F. Léger. New York: BDD Illustrated Books. ISBN 0-7924-5848-

- Artcyclopedia - Links to Léger's works

- Artchive - Biography and images of Léger's works

- Ballet Mecanique - Watch Fernand Léger's Short Film

He renounced abstraction during the First World War, when he claims to have discovered the beauty of common objects, which he described as 'everyday poetic images'. He began painting in a clean and precise style, in which objects are defined in their simplest terms in bold colours, taking cityscape and machine parts as his subject matter. In 1924 he made a 'film without scenario', Ballet Mecanique, in which he contrasted machines and inanimate objects with humans and their body parts.

During the Second World War, Leger lived in the USA where he taught at Yale, returning to Paris in 1945, when he opened an academy. His large paintings celebrating the people, featuring acrobats, cyclists and builders, thickly contoured and painted in clear, flat colours, reflected his political interest in the working class, and his attempt to create accessible art. From 1946 to 1949 he worked on a mosaic for the facade of the church at Assy, produced windows and tapestries for the church at Ardincourt in 1951, as well as windows for the University of Caracas in 1954. In 1950 he founded a ceramics studio at Biot, which, in 1957, became the Leger Museum. In 1967 it became a national museum. Leger was one of the giants of French painting this century, whose influence has been almost as great as his reputation.

- From The Bulfinch Guide to Art History

The following review of the Leger retrospective held at the Museum of Modern Art in 1998 was written by Dr. Francis V. O�Connor, Editor, O�CONNOR�S PAGE.

I do not like Fernand Lιger.

Thanks to MoMA's good enough exhibition, I have been able to come to this judgment of an artist, whose last major show in New York was in 1953, and whose work has been seen around piecemeal ever since. So I never saw enough to form an opinion. I did read Alfred Barr's famous put-down about Lιger being a noisy artist chasing fire engines, the business about him being a champion of the machine, and the clever mot about "Tubism." Now these eighty objects (the twenty drawings included are calmer and more elegant), are all lined up for inspection, and the paintings have earned their demerits -- in my eye at least.

First off, I think Barr was right; the visual noise from the walls of this exhibits rivals that of several recent shows at MoMA and elsewhere about town, of contemporary junk blaring actual noise from recordings and videos (vide Viola at the Whitney). Lιger's noise is worse, in that it rivals that felt in the eye of the French poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire by a red and green awning opposite his window. Yet even the old Op Artists were tolerable in their optical vibrancy, whereas Lιger is relentless, vulgar and visually debilitating. Further, the show is packed into MoMA's downstairs galleries, where each painting can hardly be seen without its neighbors lending their din. This is the kind of work that needs room -- but even spatial soundproofing would not redeem these ranks of visually cacophonous disasters.

As for Lιger being an artist of the Machine Age, celebrating the rise of our century's technology, I'll take Picabia, Sheeler and Diego Rivera any day. If Lιger managed to get the roar of the factory, the squeal of a drill press, and the screech of the unoiled gear, into his paintings, it was an achievement I, at least, do not much appreciate. Going through the River Rouge auto plants when I was working on an essay about Rivera's murals of the Ford assembly line for the Detroit Institute of Arts' retrospective, revealed those vibrant old factories as far more organic and chthonic, if not downright hellish, than Lιger's fantasies of the worker's environment, where everything is neat primary colors -- and the rust, heat, grunge and quaking are totally absent.

Further, the essence of a machine is its interconnectedness: one part relates to the other, and all the parts join to perform an action that is specific and useful. If you look carefully at any Lιger, you see immediately that it is an extremely complex, but fundamentally unintegrated, pattern. Nothing really connects to anything else--not even arms and legs!

As for "Tubism" and its relation to Cubism, it is too bad that he did not stay with the latter. The 1911 works influenced by the Cubists are superb. But he does not develop these marvelous paintings; rather he grew more raucous and colorful--and noisy. By c. 1914 he is deafeningly insufferable. His motif for this visual noise starts early and these works all contain a formal complex that he used over and over throughout his career -- a balancing act of small, tightly clustered forms countering large, expansive, planar forms. Early on these consisted of hands and their rows of fingers. Later, there are steps, grills, stripes, smokestacks, girders, nets, ropes and so on. The rest of the works, all using this ingenious device for inducing visual static, are the most vulgar, loud, mechanomorphic junk I have ever seen.

These paintings are portraits of a singular chaos--and if all art is, on one level, self-portraiture, they say much about Lιger that explains the overall failure of his art on any level other than irony. Indeed, if I were doing a psychodynamic study of Lιger, I would start with the origins of that infinitely elaborated stacked finger motif -- not his much-touted infatuation with a cannon during World War I -- which is too simple an explanation for the personal etiology of these curious, pesky images.

But, if you think such stuff is "fun" -- or has "edge" -- or sounds like an exciting disco -- don't miss this visually annoying exhibit.

[This review was first published on February 15, 1998]

From 1911 to 1913, Fernand Leger (1881-1955) vitalized Cubism by adding a humanistic vigor to its sharp-edged systems, and later in the decade he was fusing principles of mechanization with figurative and worldly content. The sizable gathering of his work now on view concentrates on subsequent phases, beginning in the mid-20's, and demonstrates Leger's interests in establishing potent formal rhythms and in developing monumental images suited to both an industrial era and a new society.

Selections touch on a broad range of the themes frequently associated with Leger, including ''The Grand Parade,'' construction workers, cyclists, acrobats, dancers, musicians and circus performers.

Although it is a show that points to many of the artist's ideas, it is not a show that elaborates Leger's career. For one thing, there is no representation of his achievements before 1920, generally regarded as his most significant. Moreover, the galleries include a large proportion of ceramics, mosaics and tapestries executed by others' hands, for the most part after Leger's death. In some instances, the pieces are authorized editions involving a model or plan prepared by Leger. In other cases, however, his estate authorized copies or associates assumed that the artist would have approved of their translations from his paintings to other media.

Leger himself had decidedly positive feelings toward his direct collaborations with artisans using materials that, he believed, would allow his art to touch the lives of a larger audience. The sense of celebration and optimism in his themes, as well as the exuberant handling, has always contributed to the popular appeal of his art.

The first section of paintings in the main gallery is the show's richest, with strong works recalling important aspects of the artist's goals.

His achievements with dynamic arrangements of cubes, cylinders and spheres during his ''mechanical period'' come across powerfully in ''Composition, 1923-27,'' an assertive blending of harmonious, machinelike parts that retain their volumes even though they are tightly interlocked into a flat surface.

Nearby, a compelling still life, ''The Red Compote,'' is a reminder of the way Leger applied principles of industrial design to make each crisp object a formidable presence and to build a taut but complex structure that vibrates from edge to edge.

Following a course that has become familiar in late 20th-century painting, Leger sometimes combined stylistic approaches on a single surface, correctly believing this could add intensity. ''The Dancers'' is a telling example, with a left segment holding undulating biomorphic forms representing swaying bodies and a right section devoted to geometrics suggesting a cityscape.

Reconciling characteristics of the machine with characteristics of human activity is a major issue in Leger's work, and one that is brought to the fore in the mural-size canvas, ''The Gymnasium.''

In his comments on humans, objects and their settings, Leger often combines gigantic but disparate things that lend meaning to one another. ''The Keys'' is one forceful example. Another is ''The Yellow Plant,'' a gathering of separate, weighty shapes that serves as a reminder of Leger's treatments of nature. Combining abstract and objective approaches, these paintings give an emblematic quality to their subjects and have held up especially well.

While figures tend to lose their vitality in some of the artist's reductive schemes, the plant motifs occasionally take on animated stature. This is especially clear in studies for a Rockefeller fireplace mantel and in the most successful of the ceramics, ''The Children's Garden.''

The modern rhythms in a number of crowded, energetic works from Leger's final decade relate to his observations of New York City, where he spent the war years. Interlocked bodies create tense compression in ''The Four Acrobats,'' one of the best examples of his interest in physicality, but a smaller, untitled 1952 gouache rendering of a dense pile of abstract shapes plays with weight and volume in a striking manner that seems to anticipate Philip Guston's late paintings.

1 σχόλιο:

Hello,

I'd appreciate if you can give me some feedback on our site: www.regencyshop.com

I realize that you are home decor-modern design connoisseur :) I'd like to hear your opinion/feedback on our products. Also, it'd be swell if you can place our Le Corbusier link on your blog.

Thank you,

Nancy

Δημοσίευση σχολίου