with English translation by Kitajima Yuji

Gay Erotic Art in Japan (vol. 1):

Artists from the Time of the Birth of Gay Magazines g

Fûzoku kitan, one of the most long-lived of the 'perverse' magazines published from 1960-1974. Fûzoku kitan, one of the most long-lived of the 'perverse' magazines published from 1960-1974. | Other magazines which included information about homosexual and transgender phenomena included Fûzoku kagaku [Sex-customs science] (1953-55), Fûzoku zôshi [Sex-customs storybook] (1953-4) and Ura mado [Rear window] (1957-65). While all these magazines featured articles and illustrations relating to male homosexuality, as Tagame points out, it was Fûzoku kitan [Strange talk about the sex world] (1960-1974) which showed the strongest interest in this topic and which featured the homosexual erotic art work of four of the artists introduced in Tagame's collection—Okawa Tatsuji, Funayama Sanshi, Mishima Go and Hirano Go. |

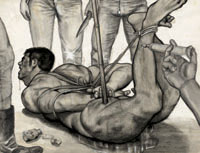

This illustration by Oda Toshimi in Fuzoku Kitan is an example of the ‘perverse’ nature of these early magazines, mixing sadomasochism, voyeurism and homoeroticism in the one image. This illustration by Oda Toshimi in Fuzoku Kitan is an example of the ‘perverse’ nature of these early magazines, mixing sadomasochism, voyeurism and homoeroticism in the one image. | term 'gay' to describe these images seems anachronistic in this context, especially given the violent and sadomasochistic contexts in which the artists placed their figures. The problem with the term gay or gei in katakana transliteration is that it was already in wide use in Japanese in the 1950s but it had a meaning quite different from the English term which was gradually emerging in the US as the most widespread designation for members of the homosexual subculture. |

Picture of a gei bôi from Tomita Eizô (1958), Gei, Tokyo: Tôkyô shobô. Picture of a gei bôi from Tomita Eizô (1958), Gei, Tokyo: Tôkyô shobô. | than today's boyish young women.'[1] The widespread use of the term gei in Japanese therefore predates the use of 'gay' in English which did not become a common referent for homosexuals (outside of specific subcultures) until the early 1970s. Another reason that gei bôi was so quickly popularized in Japan is that gei (written in the katakana syllables used to transcribe foreign loanwords) is a homophone for gei (written with the character for 'artistic accomplishment'—as in geisha) and gay boys were sometimes spoken of as gei wo uri, that is 'selling gei.' In this phrase gei designates not sexual orientation but a kind of artistic performance—female impersonation. |

|  |

|  |

Endnotes

[1] Tomida Eizô (1958), Gei, Tokyo: Tôkyô shobô, p. 181.

[2] Chigo is a term deriving from the Edo Period (1600-1857) nanshoku code of male-male eroticism. It originally designated a young temple acolyte but came to be used to refer the younger partner in a transgenerational homosexual relationship. Ka here is a suffix meaning 'specialist'.

[3] Jibika here is made up of the characters for ear and nose as in the medical 'ear, nose and throat specialist'. Perhaps an ironic reference to the fact that older men were sometimes hard of hearing. Another term was fukesen or 'specialists in older men'.

[4] Ritsu means a rate or percentage.

[5] The most valuable Japanese source for this period is Fushimi Noriaki's Gei to iu keiken [The experienced called gay], Tokyo: Potto shuppan, 2003. My own book Kono Sekai: Queer Japan from the Pacific War to the Internet Age (in press) is, to my knowledge, the only treatment in English of homosexual identity and practice in the immediate postwar period in Japan.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου